Houston’s Götterdämmerung Is a Successful Experiment in Total Work of Art

/By Truman C. Wang

5/11/2017

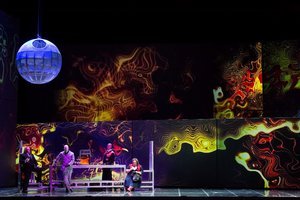

Photo credit: Lynn Lane, Houston Grand Opera

As the final saga of the Ring tetralogy, Houston’s Götterdämmerung came not four evenings after Das Rheingold, but four years. These four years saw the fanciful production concept of La Fura dels Baus mature into a cogent and powerful vehicle for Wagner’s music drama. This final opera of the Ring cycle has been likened to a French grand opera, in its sheer length and its richness of scenic and musical materials. In the Houston production, the infinitely configurable projection screens (by Franc Aleu) swivel and pivot to show Brünnhilde’s ring of fire or the Rhinemaidens’ watery world, as well as abstract images during Hagen’s Dream and Siegfried’s drinking of magic potions. The naturalistic and abstract visual elements coalesce organically and effortlessly into the musical fabric to make this Götterdämmerung an unforgettable theatrical experience – a Total Work of Art (‘Gesamtkunstwerk’) as Wagner had envisioned.

Powerful visuals abound in this artful production by the Barcelona-based La Fura dels Baus. They are achieved via a clever combination of front projection on a scrim and rear projection of six moveable panels. In the Act Two “Hagen’s Dream”, the moving projections give viewers the illusion of being drawn into the dream. Also in Act Two, the vengeance scene where Brünnhilde and Hagen are plotting to kill Siegfried is played out in front of a first-person shooter video game screen, where the mime actors drop dead one by one upon being shot. In Act One, Siegfried drinks Gutrune’s magic potion and its psychedelic effects are felt and seen on the video walls as lava-lamp graphics. Last but not least, Brünnhilde’s Immolation is a stunning montage of fire, water and a tower of acrobats that topples like the castle of the gods.

The industrial-age sets by Roland Olbeter transform the Valkyrie’s horses into a mechanical crane on a pivot operated by two stagehands. In Act Two, four of these cranes carry the boat of Brünnhilde and Gunther to Gibichung for their double wedding. The three Rhinemaidens are frolicking inside three glass water tanks suspended high above the stage, surrounded by a photo-realistic video-projection backdrop of the underwater world. Despite the modern sets, everything is logically placed, inoffensive and often beautiful to look at.

Somewhat controversial is the stage direction of Carlus Padrissa. Apart from the aforementioned shooter video game, in the opera’s ending Hagen shoots Gunther dead over the ring with a revolver. It should be noted, however, that any parallels with the current gun politics are merely fortuitous, as the stage actions follow closely the original Barcelona production from ten years ago. In the Gibichung scene, a lot of gaiety and humor is put on the character of Siegfried, from his rough redneck greeting of Gunther to his cleanup by three guys in hazmat suits. It serves as a welcome comic relief before the impending tragedy.

There is a consensus among Wagner aficionados that we do not live in the golden age of Wagnerian singing, nor did we in the past several decades. As such, we should not expect our Siegfrieds and Brünnhildes to sound anything remotely like Windgassen and Nilsson in the 1960’s. Christine Goerke is a womanly Brünnhilde, whose warmth and dramatic phrasing make up for any lack of heft or orchestra-piercing power. Simon O’Neill’s Siegfried impresses with his stamina and acting chops, even manages to sing while hanging upside down in the Act Two oath scene. As Hagen, bass Andrea Silvestrelli’s woolly, unattractive, back-of-the-throat style of vocal production is completely in character as the evil, sinister son of the Nibelung. The Three Rhinemaidens sing with winsome charm and the Three Norns are also excellent. The finest singing comes from the Waltraute of mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton (also Second Norn) and the Gutrune of soprano Heidi Melton (also Third Norn), both of whom deservedly steal thunder from Brünnhilde in their scenes together.

Conductor Patrick Summers is, in many ways, the star of the show, drawing some unforgettable playing from the Houston Grand Opera Orchestra to rival the best symphony orchestras. Certain passages could be tauter and punchier, as in the Act Two oath or Siegfried’s Rhine Journey (which sounds humorously like a marching band), but overall the long scenes are beautifully paced with the leitmotives weaving and fusing into one another in one smooth symphonic fabric. The Siegfried’s Funeral March is the orchestra’s finest hour and played with tremendous gravitas and power in a ten-minute-long procession to honor the tragic fallen hero.

Truman C. Wang is Editor-in-Chief of Classical Voice, whose articles have appeared in the San Gabriel Valley Tribune, the Pasadena Star-News, other Southern California publications, as well as the Hawaiian Chinese Daily. He studied Integrative Biology and Music at U.C. Berkeley.