Santa Fe Opera, Summer of 2023 In Review

/By Truman C. Wang

8/21/2023

Photos by Curtis Brown, Santa Fe Opera

I spent a week in Santa Fe, New Mexico, seeing four operas from August 15 to 19. The indoor-outdoor design of the Santa Fe Opera House is an engineering and acoustical marvel. As you drive north on Highway 84, past Exit 168, the distinctive curvature of the opera house roof looms on the hilltop like a desert mirage, or a house of worship for the opera faithfuls. Not all, but many, opera directors have taken advantage of this unique venue by incorprating nature as part of their scenic design. Fun facts: The city of Santa Fe is the oldest U.S. state capital, founded by the Spanish in 1610, three years after the first performance of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607), and ten years after the first opera Euridice (1600). The Santa Fe Opera’s young singers apprentice program rivals that of San Francisco Opera and the Met in graduating world-class artists (Nicholas Brownlee, Joyce DiDonato, Samuel Ramey, et al.) The audience here are generally more knowledgeable and conscious of operatic etiquette, such as arriving on time (shows start promptly within 5 minutes of advertized time.) and not unwrapping candies during the performance. There are also standing room tickets for $15 with good view of the stage. Food options are plentiful but that’s going to be a separate blogpost.

Now, let the shows begin…

“The Flying Dutchman”, Stormy Sea Meets Wild West

The Santa Fe Dutchman, with industrial cargo ship nautical-themed décor by Paul Steinberg and Brendan Gonzales Boston, and colorful Western costume by Constance Hoffman, is not especially outré by today’s standards; nonetheless, the production has compelling theatricality that one usually finds in old-fashioned picturesque stagings of Wagner’s early operas. Here, the only picturesque element is supplied by the glowing embers of Santa Fe’s gorgeous sunset.

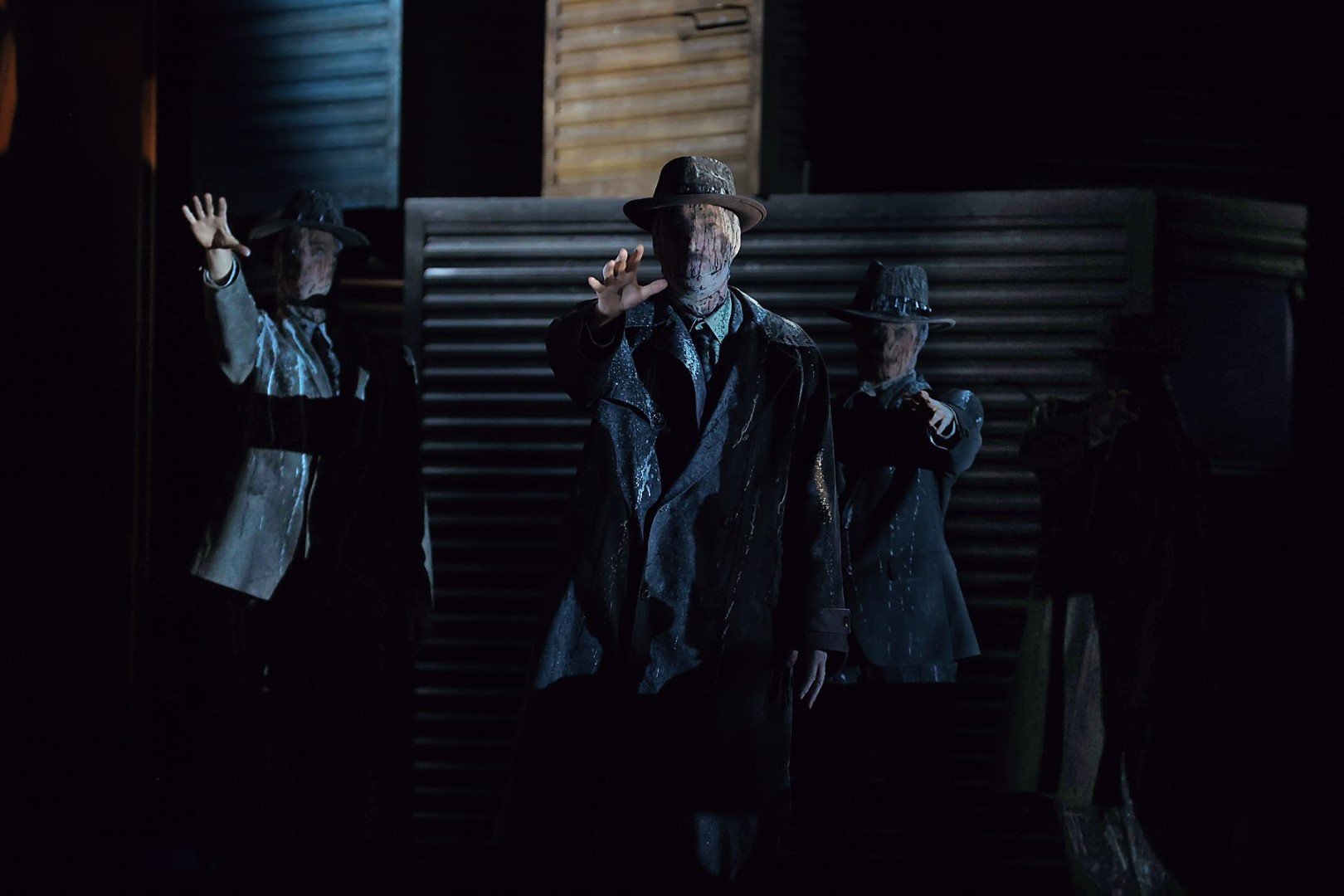

David Alden’s direction is effective, entertaining and, for the most part, as Wagner prescribed. Senta “starts up from her seat, carried away by sudden inspiration” to sing the end of her ballad (in many productions she is already standing.) Daland’s sailors are rowdy cowboys happy to sing a shanty song and itching for a bar fight; The Dutchman’s ghostly sailors are bronze cowboys that move like zombies; Senta’s village girls don yellow overalls and now work as ship mechanics. The choruses are required to act and emote more in this staging than most others I have seen, and they did a superb job.

The opera was played with one twenty-five minute intermission after act two, and ended in a crucifixion of sorts for Senta, in stage center, roped by four criss-crossed tow lines, while the Dutchman’s ship sank behind her. Elza van den Heever, the Senta, was in splendid voice and sang with the creamy legato line and pathos of a belcanto heroine. (One could draw a parallel between Senta’s anguished reply in her duet with the Dutchman, and Elvira’s heartbreaking reply “Tre secoli” to Arturo in I Puritani.) Nicolas Brownlee, the Dutchman, sang soundly in his first major Wagnerian outing. Morris Robinson’s smooth-singing Daland was a welcome comic relief. The thirty-year-old German conductor Thomas Guggeis gave a thrilling, yet nuanced, reading of the score.

“Orfeo” in New Garb, Looks and Sounds Stunning

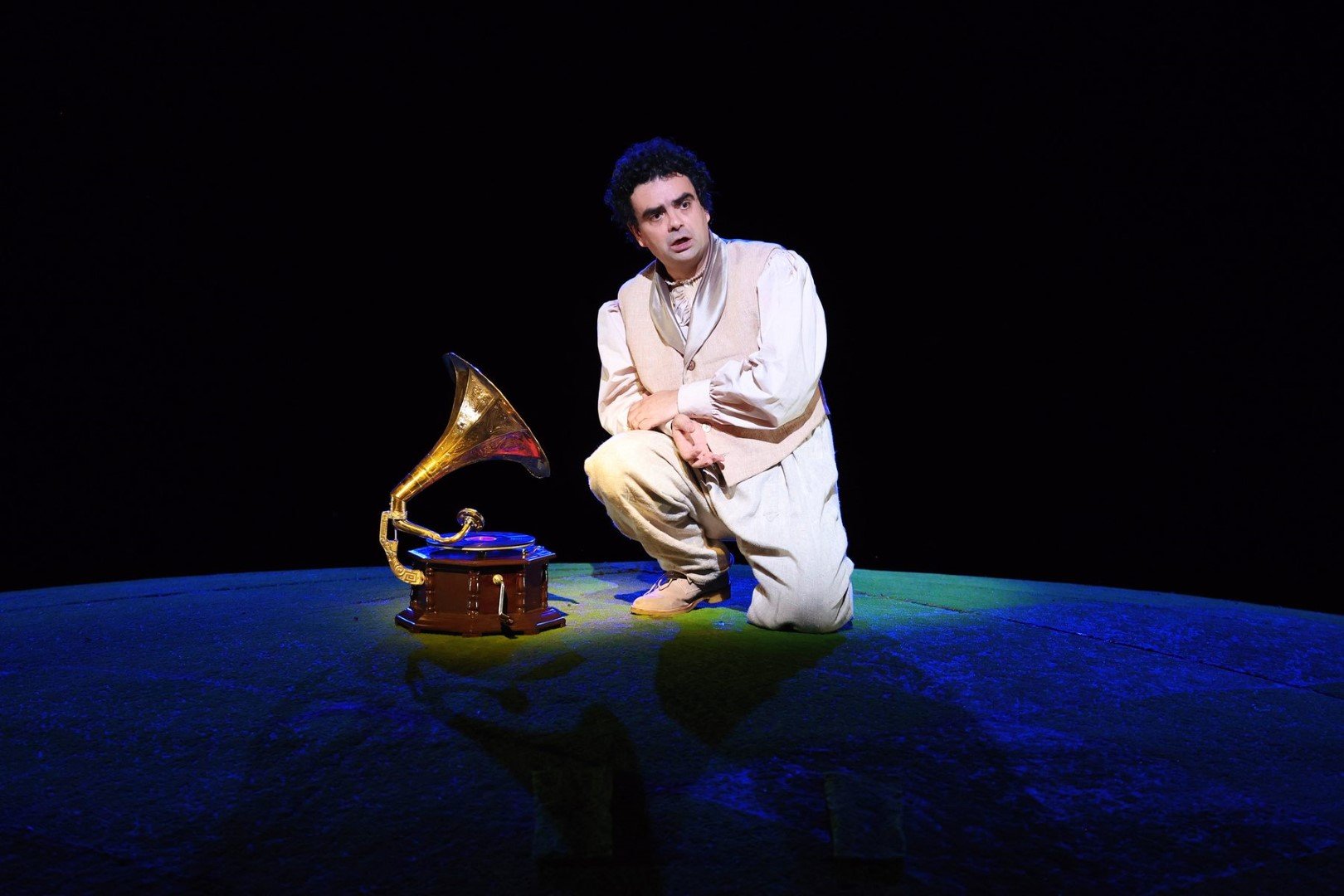

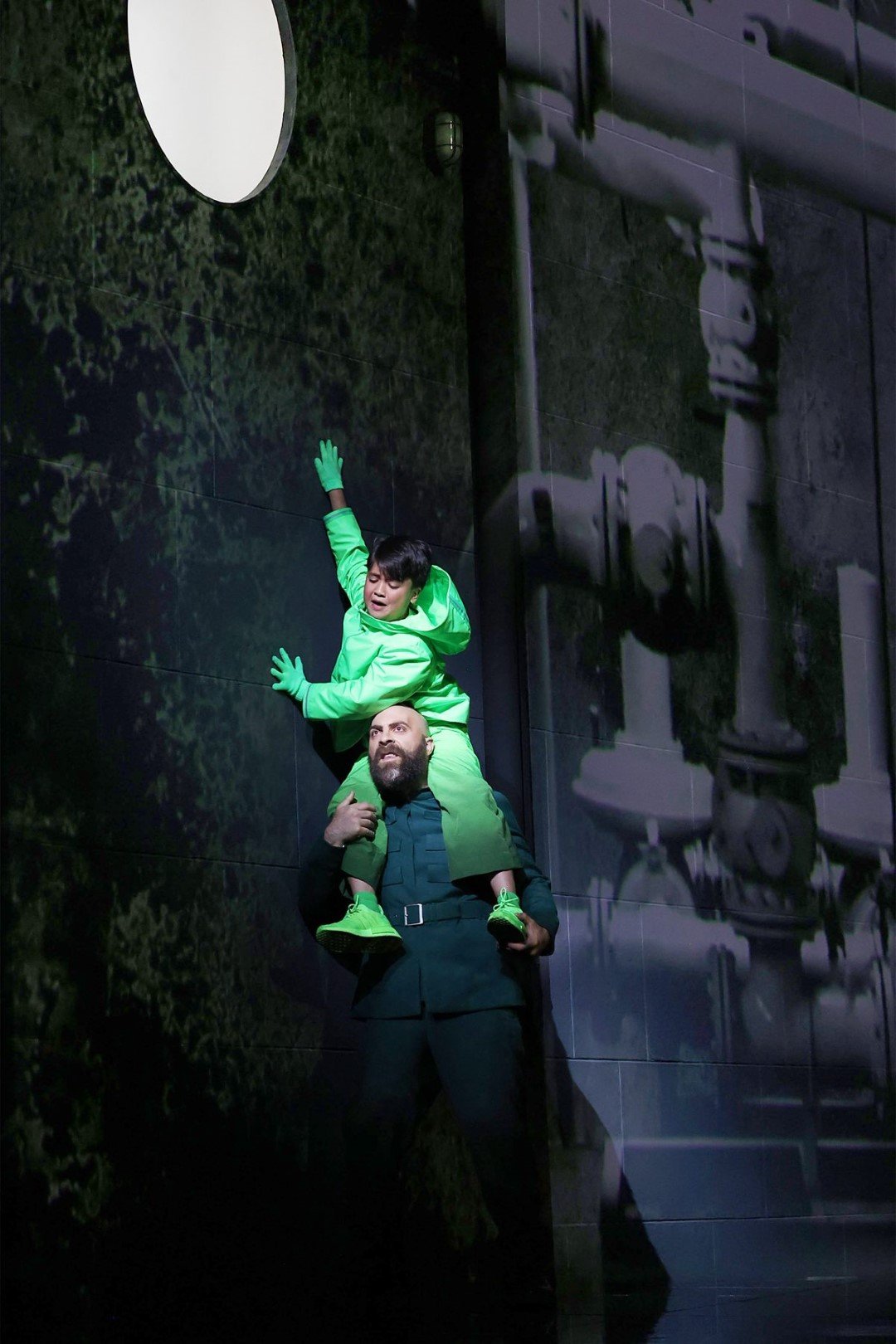

Much of the Romantic and Renaissance literature has to do with the artists’ relationship with nature. Whether serendipitous or not, during the announcement of Euridice’s death, there was a huge thunderclap, followed by a series of lightening flashes, as if the god of the underworld Pluto was announcing his presence. There was nothing, however, Rolando Villazón, the Orpheus, could do to impress Pluto and get his new bride back – by singing beautiful long, long melismas with slancio and ringing squillo, or doing somersaults in the air like a Cirque du Soliel aerialist, in a mesmerizing laser light extravaganza showing him descending into Hades. It was an unforgettable coup de théâtre from the American director Yuval Sharon and possibly his finest work to-date.

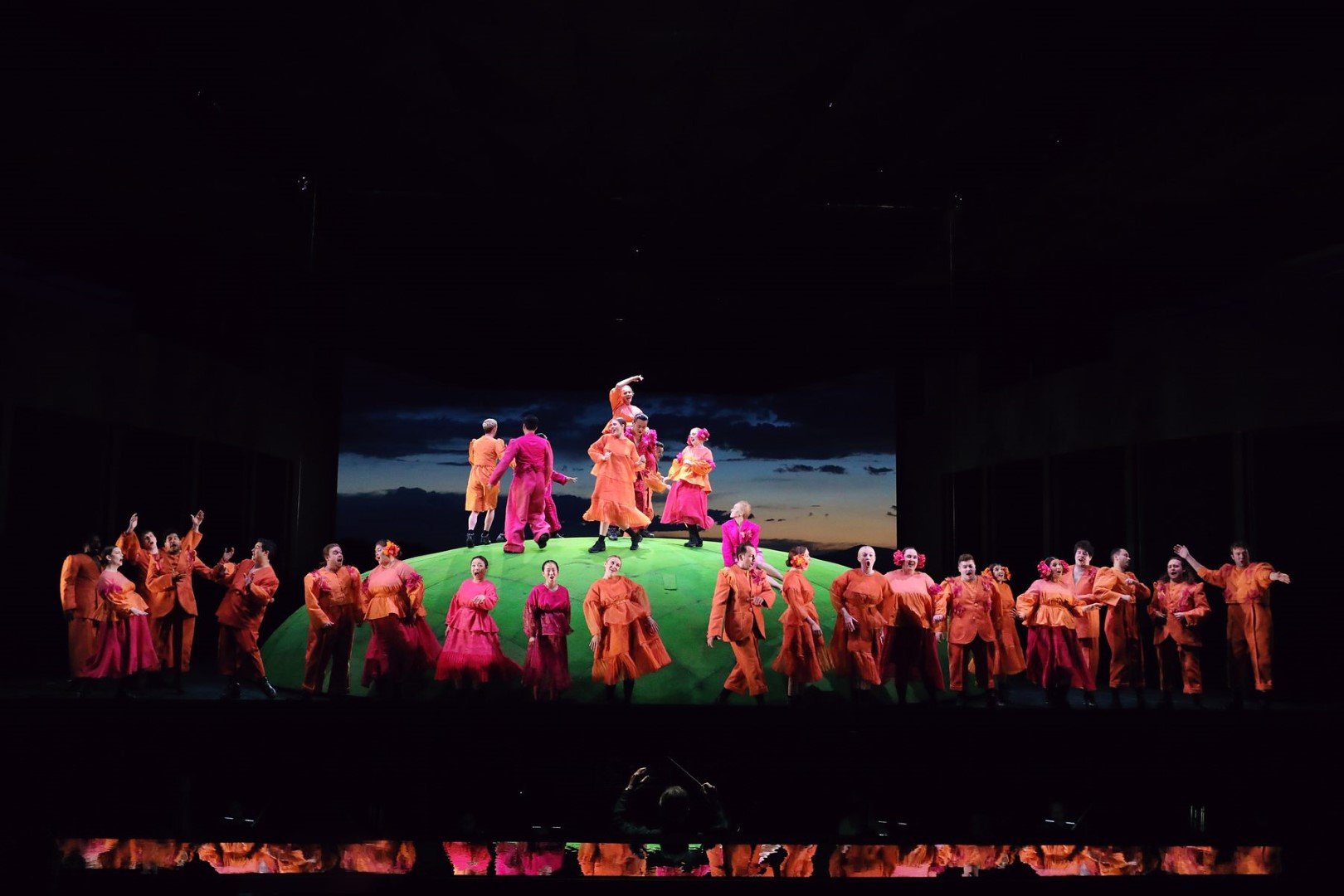

There were many more such memorable, endearing stage pictures in this Orfeo. During the wedding celebration, the blindfolded Orpheus frolicked with the villagers; a group of villagers wore animal heads like a scene from The Midsummer Night’s Dream or Falstaff. (There was also a badminton game thrown in there somewhere.) And then there was that giant dome that served multipurpose – as a happy wedding venue, and as a gaping mouth of hell. At one point, through tricks of lighting (by Yuki Nakase Link), the dome was even turned into a mini Vegas Sphere! But since we were in New Mexico, the dome could also be made to look like a mesa, complementing Carlos J. Soto’s Southwestern costume for the villagers.

The first performance of L’Orfeo, 416 years ago, took place in a small room of Duke Vencenzo Gonzaga’s palace, with audience numbering barely more than the performers. Monteverdi himself reportedly wasn’t too happy with the limitations of the tiny venue, which necessitated him to substitute a short tragic ending and called it the night (not the Apollo happy ending we know today which requires elaborate stage machinery.) For the Santa Fe performance, composer Nico Nuhly worked closely with conductor and early music specialist Harry Bicket (also Santa Fe Opera’s Music Director) to re-orchestrate the opera (now renamed Orfeo) for modern consumption, the result being a true revelation and an unqualified success. The best thing I could say about the new score is that it is unobtrusive, preserving all of Monteverdi’s vocal lines but often accentuating them with modern harmonies and orchestral colors. The ritornello music, for example, changes its tone and color, in dramatic context, each time it returns. The orchestra played splendidly under maestro Bicket.

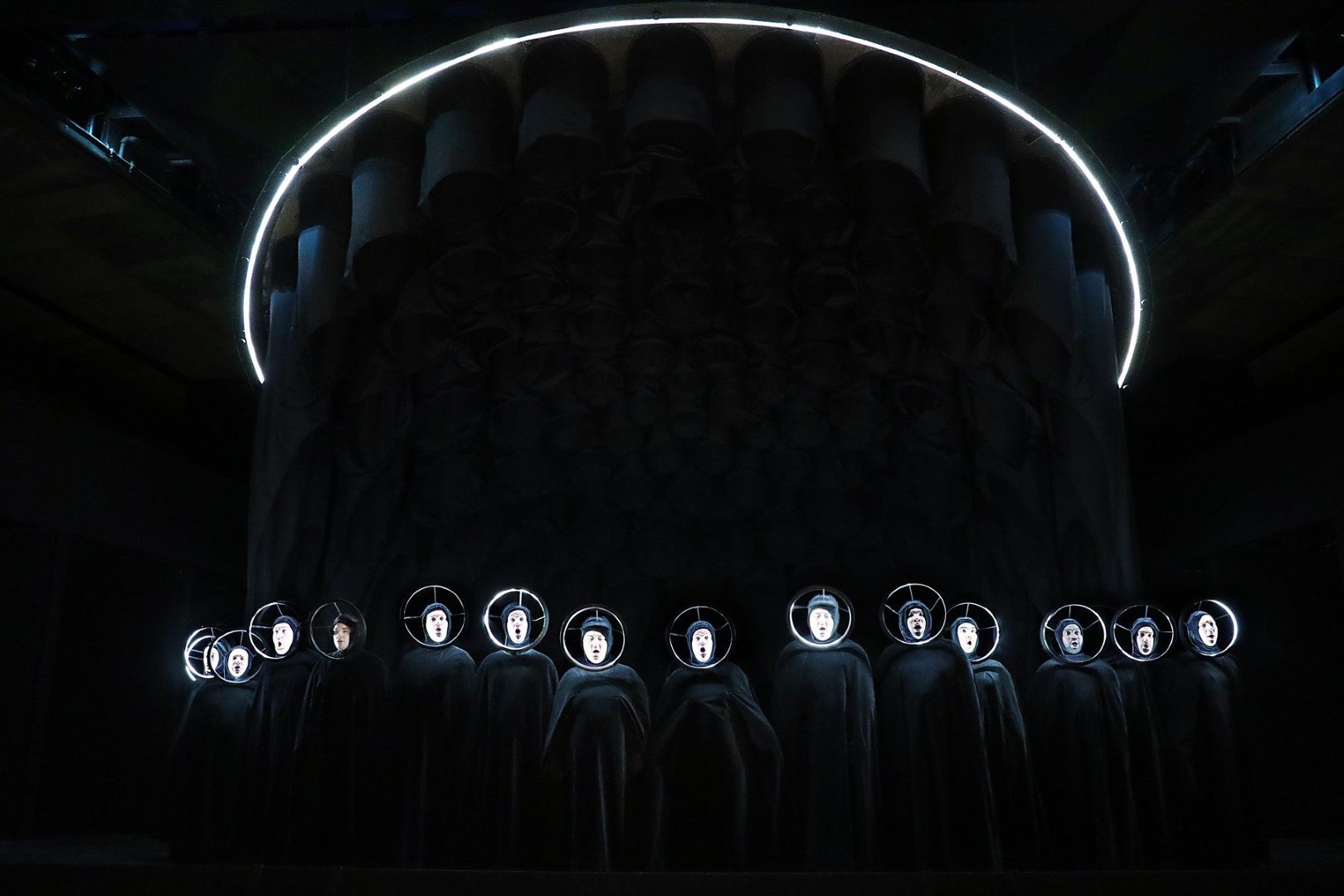

The singing was also accomplished, apart from Villazón, there were Lauren Snouffer, as La Musica/Speranza, who introduces the opera; and bass James Creswell, as Charon. Three tenor shepherds were excellently and agreeably audible (unlike countertenors used in other productions). The Santa Fe Opera Chorus again outdid themselves with precise singing and fun acting. All the singers conveyed the words and emotions with passion and vividness.

In true Bayreuth-style, a brass band played the opening flourish from the opera to usher in the patrons: first outside the gate, second time from a balcony, and last time on the terrace.

“Rusalka”, a Fairy Tale Turns Grimm

After the Dutchman and Orfeo, this Rusalka staging by David Pountney, with abstract modernist sets by Leslie Travers, is decidedly anti-nature. No mermaids, no trees, no lake, no moon, and no open backdrop of the Santa Fe hills, which on this evening of raging storm and howling winds probably did not matter. Before the show started, audience members scrambled to move to ‘indoor seats’ or open their umbrellas in their ‘outdoor seats’ – an interesting phenomenon. In Los Angeles, I only recall one concert at the Hollywood Bowl that had a sudden downpour, soaking the entire audience (and the conductor joking about playing the Water Music.)

Dvořák’s Rusalka (1901), the ninth of his ten operas, is a lovely work – melodious, emotional, picturesque, and richly scored. The “lyrical fairy tale” combines La Motte Fouque’s Undine and Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. The opera is essentially a series of dreamlike scenes, or a beautiful tone poem with contrasting movements.

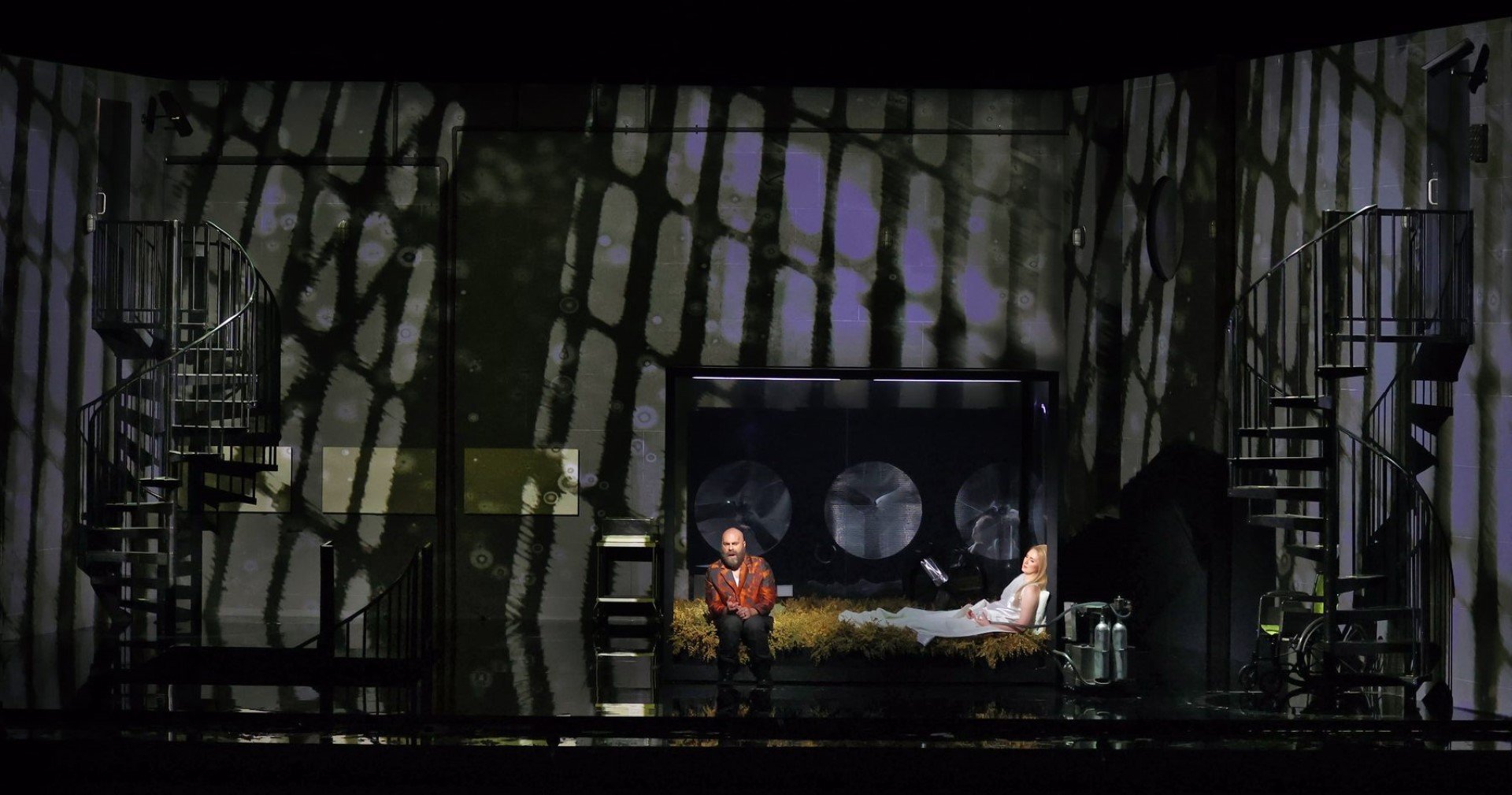

Director David Pountney also treated it as a fairy tale, not Andersen’s, but Grimms’. Jezibaba throwing a cat into her magic potion stew, later knifing Rusalka until her white gown was drenched in blood, the servants chopping up game fowls and playing with their innards – hopefully no kids were in the audience. The all-white sets by Leslie Travers shows extreme mental distortion and abstraction of reality – a chair ‘tree’, glass display cabinets showing nature and animals as man’s trophy. It was, as the old lady sitting next to me admitted, “all very perplexing.”

Lidiya Yankovskaya, hailing from St. Petersburg, Russia, gave a reading that was the musical antithesis of the staging – beautiful, lyrical and picturesque (kudos to to the excellent, dreamy flute playing!) Ailyn Pérez, the Rusalka, onstage throughout the long opera (but silent in most of act two), has a fine soubrette voice, very clear and bell-like, fitting the prince’s description of her as a “cold and icy beauty,” unfortunately Rusalka’s Hymn to the Moon needed more finesse and emotion. Robert Watson, the prince, was forthright and romantic, marred only by an overly-histrionic dying scene. Raehann Bryce-Davis, the witch, and Mary Elizabeth Williams, the Isolde-size evil princess, looked the part and sounded splendid. James Creswell’s goblin was gravely moving. Jordan Loyd and Tessa Fackelmann stole the show as two zany servants.

“Pelléas et Mélisande”, Mystery Theater with Genuine Human Drama

Pelléas was directed by Netia Jones, who also designed the décor, costume and video projection showing woodsy and watery settings depicted in Maeterlinck’s scenes and Debussy’s music (dark forest, misty ocean, sparkling lights inside grotto, etc.) while occasionally giving commentaries on the drama (black bars during Mélisande’s song showing her as a caged songbird). D.M. Wood’s atmospheric lighting contributed to the eerie mystery that enshrouds this unique opera.

There were odd staging directions. The actor doppelgangers mirrored the characters’ actions but contributed nothing dramatically. The servant in the final scene replaced inexplicably by Genevieve, therefore making nonsense of Golaud’s derogatory comment about the servant. But by and large, the director restricted her heavy symbolic underlining to the décor and video projection, and presented a drama played by “real people”. Samantha Hankey was a fine Mélisande, a straightforward, credible, touching young ray of light. Her singing was a mixture of tart and sweetness. Huw Montague Rendall, the Pelléas, had the same youthful directness. Gihoon Kim (Golaud), Ben Brady (Arkel), and Emma Rose Sorenson (Genevieve) were all distinguished. Kai Edgar, the well-traveled Yiniold who appeared in L.A.’s Pelléas in March, was more audible from the Santa Fe stage. Here he was presented as a real boy and not a caricature in L.A.’s McVicar staging. Harry Bicket’s musical direction was at once sensitive and sensible, reaching Wagnerian intensity at times. Kudos also to the lovely flute and harp playing that added much welcome glimmers of light to this dark, mysterious score.

Truman C. Wang is Editor-in-Chief of Classical Voice, whose articles have appeared in the Pasadena Star-News, San Gabriel Valley Tribune, other Southern California publications, as well as the Hawaiian Chinese Daily. He studied Integrative Biology and Music at U.C. Berkeley.