Wagner’s Rhine Gold Shines Brightly in Disney Hall

/By Truman C. Wang

1/21/2024

Photo credit: Timothy Norris | LA Phil

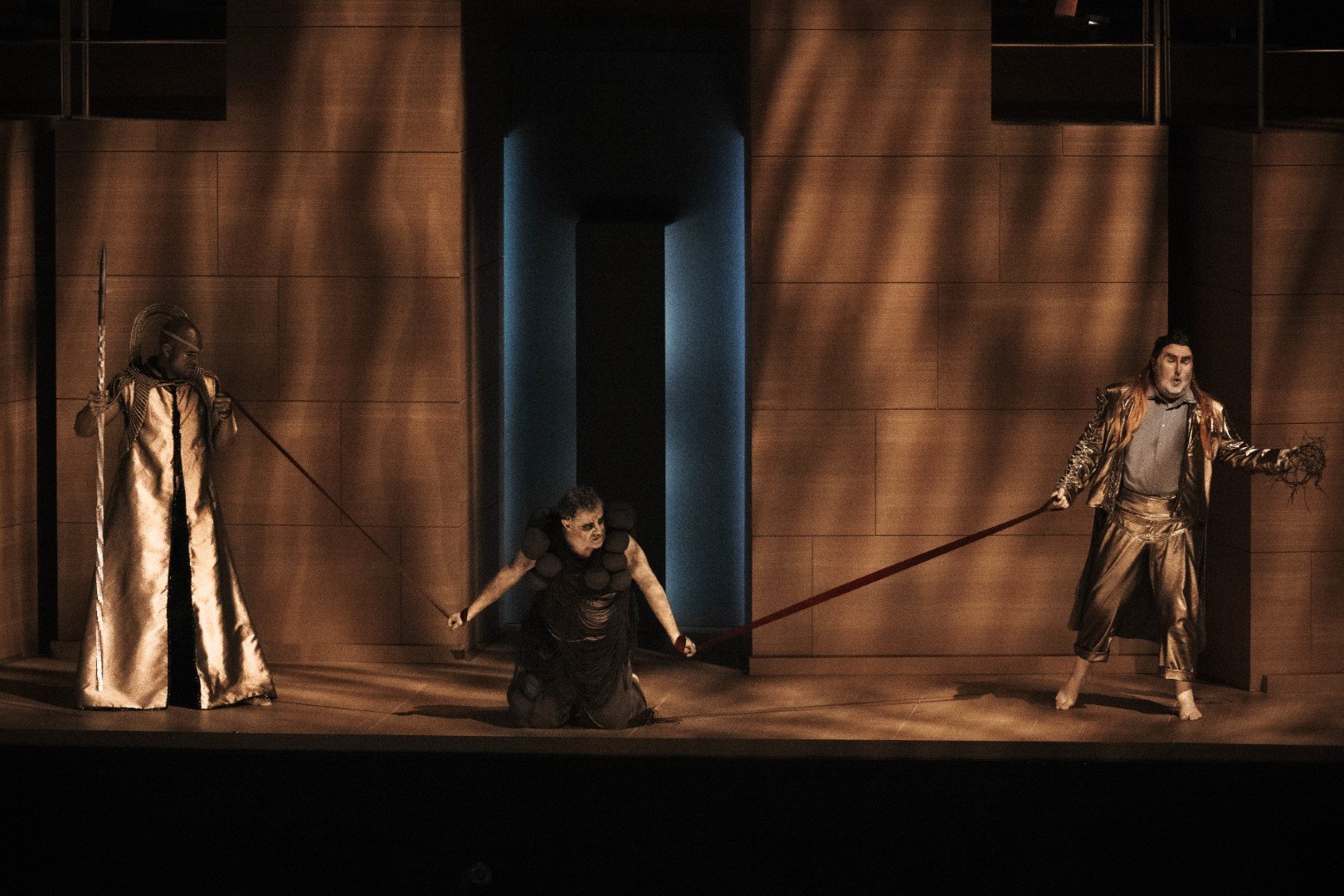

The LA Phil’s concert presentation of Das Rheingold in Disney Hall this week looks, in musical parlance, badass. Frank Gehry, the hall’s architect, reconfigured the concert stage into an opera house’s orchestra pit. The actions take place on the platform stage above the pit, as well as a circular ring on the front of the pit (an opera house cliché that’s increasingly commonplace today.) The ‘scenery’ consists of six tall parapets, color-matched to the hall’s wood paneling, and five fabric panels for video projection of fire and water imagery.

Director Alberto Arvelo wrote of the production in the program note, “[it] does not take place in a particular period of time, nor in a defined culture; it is an abstract metaphorical journey.” Cindy Figueroa’s beautiful costumes certainly needed no explaining or imagining – the three Rhinemaidens wore vivid shades of marine blue, frolicking on the parapets, while Alberich tried to catch them from below. Freia wore a bridal gown. Wotan and Fricka (both played by African-American singers) were dressed in what looked like ethnic African clothing. The giants were positioned on opposite ends of the parapets. Erda emerged from the front ring. Gods and dwarfs moved about freely and constantly on the platform level and often out onto the front ring. Rodrigo Prieto’s ‘ambient lighting’ LED strips on the floor, subtle but effective, changed to red, blue or green depending on the emotional content of a scene.

Other parts of the staging required more imagination on the part of the viewer. The giants looked not at all big nor menacing; Alberich’s transformations into a big serpent and a tiny frog were left entirely to the imagination; there was no chorus of screaming Nibelungs (a big letdown); last but not least, the rainbow bridge to Valhala at the end was only suggested in rainbow-colored ambient lighting.

The assembled cast was culturally diverse and vocally variable. Only three singers stood out as being exceptional: Simon O’Neill’s Loge, Jochen Schmeckenbecker’s Alberich, and Ryan Speedo Green’s Wotan. Green was a noble and youthful-sounding Wotan, as he should be at this early stage of the Ring saga. Raehann Bryce-Davis’ Fricka was a lady protesting too much, emoting heavily, resorting to sobs and chest tones as if she was singing Italian verismo. Tamara Mumford, a fine mezzo-soprano in other roles, was miscast as Erda, a role that calls for a weighty contralto. John Matthew Myers sang Froh’s two ariettas sweetly, but is hardly a herioic tenor that the role needs. (Wanger’s first Bayrueth Froh also sang Siegfried.) Peixin Chen’s Fafner had less heft and volume than Morris Robinson’s Fasolt; the two should switch roles. Jessica Faselt’s Freia was pure-voiced in a bridal gown. The three Rhinemaidens were spiky, sounding overparted rather than harmonious.

The role of Loge, god of fire, may be a secondary role in Rheingold, but the singer playing him should be a true heroic tenor and not a spieltenor (a character tenor). He has the longest solos and must have big vocal resources. Wagner’s own first Bayreuth Loge – Heinrich Vogl – was a Tristan, a Siegmund, and a Siegfried; he was also an Otello and an Aeneas in The Trojans. Simon O’Neill, a San Francisco Lohengrin, filled the bill. He played Loge with appropriate charm, wit and airy grace.

Gustavo Dudamel conducted, Bayreuth-style, entering the pit in the dark without applause. Breadth of vision, spiritual force, profundity of emotion play a large part to his maturing Wagner interpretation. Admirers of Levine, Solti, and Karajan would be ready to acclaim Mr. Dudamel’s virtues. He obtained detailed and powerful orchestral playing from the L.A. Philharmonic. He had keen feelings for the details and leitmotifs of the music, as well as the sense of epic events that, in the words of director Arvelo, “extend far beyond the drama of the characters.” He stirred the pulse and the soul of his listeners. There were six harps in the orchestra (and a solo harp backstage for the Rhinemaidens’ lament), eight horns (four of the players also played Wagner tubas), and Nibelungs’ anvils chiming in from the upper balcony. The orchestral sound emanating from the ‘pit’ was deep, rich, warm and glorious.

Truman C. Wang is Editor-in-Chief of Classical Voice, whose articles have appeared in the Pasadena Star-News, San Gabriel Valley Tribune, other Southern California publications, as well as the Hawaiian Chinese Daily. He studied Integrative Biology and Music at U.C. Berkeley.