Brief Encounter With Conductor Anton Gakkel in St. Petersburg, Russia

/By Raymond Beegle

3/26/2019

The Great Hall, resplendent with chandeliers and Corinthian columns, houses the magnificent Saint Petersburg Symphony Orchestra. Formerly the Hall of the Nobility, it has a formidable past peopled with the greatest European personalities, artists, composers, scholars, as well as the monarchs and tyrants that held them in their grasp. It seems haunted still by the ghosts of Mussorgsky, Tchaikovsky, and Shostakovich, their superlative accomplishments, and their standards of excellence. Excellent indeed was the concert I had heard a few weeks before this interview, when another conductor, Vladimir Altshuler presented a program of Dvorak, Liszt, and Tchaikovsky. The house was filled with an intelligent and attentive audience, and the performance had a ring of authenticity, vibrant with the pure joy of music making.

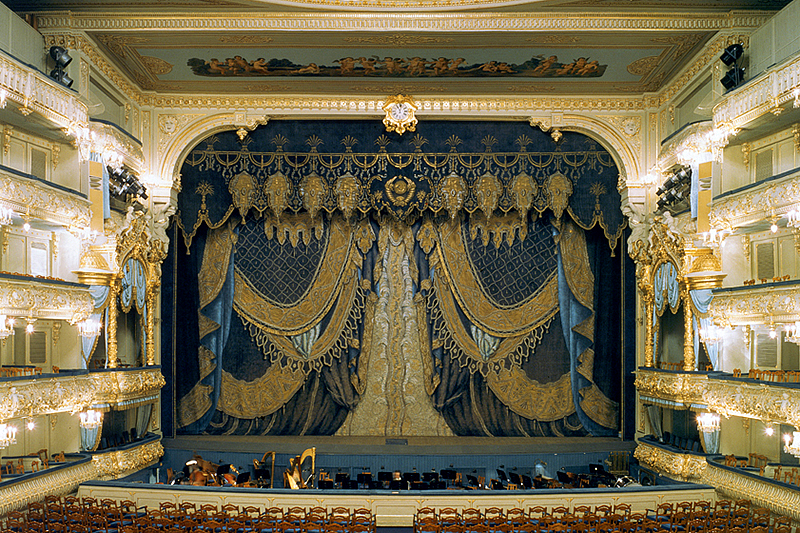

Anton Gakkel, whom I subsequently met on January 3 in a small room adjoining the main hall, is currently presenting a series entitled “The Mariinsky Orchestra: Soloists and Youth.” I very much looked forward to hearing his views on both soloists and youth, about his own youth as well, and about his attitude toward Russian culture, especially regarding the future of the great orchestras of Saint Petersburg. The busy maestro, who kindly agreed to an interview between two performances, greeted me with the polished affability characteristic of a man who deals with a host of people answerable to him, and a smaller but more daunting number of people to whom he is answerable.

On early inspirations

The common introductory questions that usually set an interview spinning, such as ‘what is your earliest memory of being moved by music,’ or ‘how did your decision to commit yourself to music change your life,’ were strangely inapplicable. There seems to have been no inspiriting first encounter, no decisive moment of commitment. “I was born into a family of musicians and I’ve always been involved with music.” “I suppose my first memorable musical experience was my father’s taking me to hear Mravinsky conduct the Eroica. It made an impression on me.” Gakkel proved to be a man of strong opinions and few words. When asked about the personalities and virtues of the three 20th century giants Furtwängler, Mravinsky and Toscanini, he replied “Toscanini was the best. He was a cellist;” Furtwängler, “slow and pedantic;” Mravinsky, “monumental.”

Anton Gakkel is also a cellist, and like Yehudi Menuhin in his later years, appears as soloist as well as conductor. Menuhin remarked “I never felt a day was complete unless I practiced the violin.” When I told this to Maestro Gakkel and asked if he practiced the cello every day he said “no.”

On literature

When I asked him to comment on Tolstoy’s controversial essay, What is Art?, I received an astonishing response. “What essay?” he asked. I repeated (in Russian) the title of the celebrated work and he replied “I don’t know this essay. I never heard of it. I don’t like Tolstoy! He’s too stern! He’s too complicated!” We moved to literature in general, about works that had a profound influence on his world view. He mentioned Suvorov’s Icebreaker, Victor Hugo’s 1793, and finally, short stories of the American Jack London, all read in his early school days. He found Icebreaker “interesting;” 1793 better than Les Misérables – “It’s shorter;” and Jack London’s stories “good because they plunge you right into his world.”

On the business (and politics) of music

On certain other subjects, answers remained succinct but not quite as incisive. I quoted Philip Glass who said “My father ran a record store, so the first thing I learned about music was it’s a business,” and Schubert, who wrote “…what God has given to me I give freely to the world, and that’s an end of it,” What was Maestro’s position? The short reply, accompanied by a hand gesture that suggested a ship maneuvering through icebergs, was “well…you live, you find your own particular place.”

As he was conducting two performances of film scores on the day of our conversation, I wondered what Mravinsky would have thought about his great orchestra playing the music of Hollywood. Another gesture, a shrug of the shoulders, accompanied the observation “well… James Horner (composer of the music for the movie Titanic) writes some good melodies.”

Regarding his current series, “The Mariinsky Orchestra: Soloists and Youth,” announced on the theater’s website, he had little to say. He mentioned his advocacy for the 28-year-old pianist Sergei Redkin. “He’s very talented.” As for youth, their tastes and development, and the future of music that lies in their hands: “Well… I guess we’ll have to wait and see.”

It appeared that neither Beethoven, nor Toscanini, nor Mravinsky, nor the cello, nor the future of music aroused much enthusiasm in Anton Gakkel. The interview came to an end. The maestro proceeded to the next task assigned him by that powerful establishment whose business it is to provide music for the city’s prominent theaters. Impersonal, labyrinthine, with roots reaching deeply into money, politics, vanity, it sometimes produces excellence, but it often stifles the spirit of gifted artists. I recalled Thoreau saying “In my experience, nothing is so opposed to poetry – not even crime – as business.”

Raymond Beegle reviews classical music and opera for the New York Observer and Fanfare Magazine. For many years he was Contributing Editor of Opera Quarterly, the Classic Record Collector (UK), and also appeared on The Today Show (NBC) and Good Morning America (CBS). As an accompanist, he has collaborated with Zinka Milanov and Licia Albanese. Currently Mr. Beegle serves on the faculty of Manhattan School of Music in New York City.