A tale of two Elviras - Seattle Opera's triumphant staging of a belcanto gem

/By Truman C. Wang

Published: 5/14/2008

Photo credit: Rosarii Lynch, Seattle Opera

Seattle Opera’s long-standing reputation as the Bayreuth of the West has not meant a dearth of fine singers for the belcanto operas. For from the truth! Its biennial International Wagner Competition is a hotly contested proving ground for aspiring heldentenors and dramatic sopranos. Its Young Artists Program, on the other hand, has had a stellar track record of producing some of today’s finest belcanto singers – perhaps none finer than Lawrence Brownlee, the Arturo in the current production of I Puritani. Richard Wagner himself embraced the belcanto style, as evidenced in his 1837 essay praising “Bellini’s pure melody – his simple, noble and beautiful cantilena”, as well as in his writing of a trill into the Valkyrie’s battle cry (although I have yet to hear it thusly sung in the theater).

McCaw Hall

Vincenzo Bellini’s I Puritani (1835) is a seminal watershed work in Italian opera. It influenced and predated later works of Giuseppe Verdi, for example, with its use of bass-soprano duets (Giorgio/Elvira’s in Act 1), its attempt at incorporating the chorus into dramatic actions, and its liberation of the traditional cavatina-cabaletta formula through superb dramatic devices known as the ‘mad scene’ (of which there are no fewer than three in I Puritani). This last feature works by freeing up the traditional form through various asides and interjections by other characters and the chorus, all commenting on the plight of the delirious heroine (At times Elvira’s Act 2 mad scene sounds more like a trio for soprano, baritone and bass). The basic slow-fast sections are still recognizable, except they are now serving a singular purpose of dramatizing the heroine’s deranged mental state. This ‘mad scene’ device of projecting lyrical pathos had worked so well in the theater that Verdi used it for his Lady Macbeth as well as Violetta (who is ‘mad’ about Alfredo in Act 1)

A Bellini statue in Catania, Italy

Even among Bellin’s own works, I Puritani is a unique masterpiece. Unlike Norma and La Sonnambula‚ both of which stand or fall on the soprano singing the title role‚ I Puritani is an ensemble piece and needs a really fine cast (Caruso’s famous admonition, “Il Trovatore needs four greatest singers in the world”, also applies here). In Bellini’s days, the ‘Puritani quartet’ comprised of, indeed, four greatest singers of the time – Giulia Grisi (Elvira)‚ Giovanni Bastista Rubini (Arturo)‚ AntonioTamburini (Riccardo) and Luigi Lablache (Giorgio). In the 1950’s, we had Maria Callas, who all but single-handedly brought I Puritani back to the repertoire through the sheer drama and charisma of her singing. Then, in the 1970’s, we had a superb ‘Puritani quartet’ again with Sutherland, Horne, Pavarotti and Ghairov. Today, I Puritani is firmly established as a staple work in the repertoire. The only problem is for opera companies to find an ideal cast, or at least the ideal soprano.

Speight Jenkins, Seattle Opera’s General Director, says he has waited 25 years to do I Puritani. He finally struck gold in finding, not one, but two extraordinarily gifted sopranos to share the role of Elvira, as well as three other excellent singers to complete the quartet. Just as remarkable is the fact that three of these singers all hailed from Seattle Opera’s own Young Artists Program. With vocal riches such as these, I would not be surprised if Jenkins decides to do one belcanto opera every season from now on.

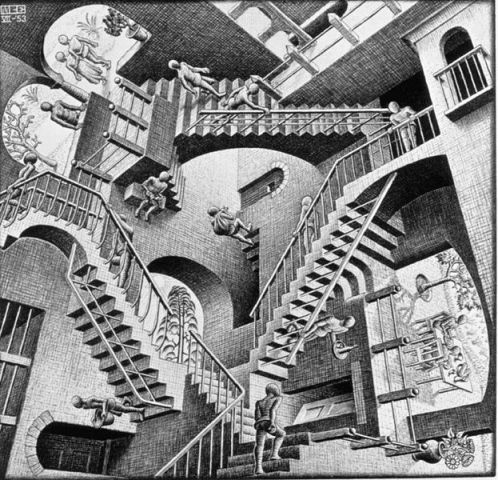

Peter J. Hall’s 30-year-old costumes for the Met still look gorgeous, evoking the lush romanticism of the opera’s English Civil War period. The original Ming Cho Lee sets, also classically beautiful, are not used. Instead, Seattle Opera’s resident designer Robert A. Dahlstrom created a massive steel modern castle, inspired by M.C. Escher, with split-level platforms connected by a jumble of straight and circular staircases that look more like a math puzzle than a real building. It all makes sense when one considers the opera’s heroine who, in her state of delirium, perceives an improbable sense of reality.

M.C. Escher's Relativity, 1953

Robert A. Dahlstrom's set design for I Puritani, 2008

The May 10th performance featured a steller ensemble cast, led by French soprano Norah Amsellem’s beautifully sung and acted Elvira. In her first foray into Bellini, Amsellem did a commendable job of balancing drama with vocal resources to create a believable character out of Elvira. Amsellem is no coloratura soprano in the manner of Natalie Dessay, but a full lyric soprano with strong coloratura pretensions. As such, the strengths of her performance lied not in the virtuoso showpieces (“Son vergin vezzosa”, “Vien diletto”), but in her superb rendering of Bellini’s long cantilenas (“Qui la voce”) and her dramatically accented phrasing of Count Pepoli’s words. In the Act 1 Elvira-Giorgio duet (a precursor to the Violetta-Germont duet), Elvira hears the commotion of her beloved Arturo’s arriving entourage and tells Giorgio to be quiet (“Taci!.. Ah patria mio!”) Amsellem uttered those words with the impetuous fervor of a woman madly in love. And in the Act 2 Mad Scene, her impassioned off-stage delivery of “Rendetemi la speme…o lasciami morire” (“give me hope or let me die”) was emotionally shattering. Physically, Amsellem is a most believable actress as well, meltingly sweet in her Act 1 encounter with Arturo and devastatingly distraught when ripping out flowers from her wedding bouquet upon learning Arturo’s alleged betrayal. Despite some intonation problems with sustained high notes, Amsellem came through triumphant in her portrayal of Elvira as a flesh-and-blood character.

The Elvira for the May 11th (Mothers Day) matinee was Cuban-American soprano Eglise Gutiérrez, who is a bird of a different feather altogether – a true coloratura canary with the warmth of a light lyric soprano. Physically, Gutiérrez is small in frame but possesses a fine sense of dramatic timing, as when in Act 1 finale she portrayed Elvira’s mental disintegration from panic to madness with complete credibility. Elvira’s “Vieni al tempio” was sung haltingly in a hauntingly elegiac tone. In Act 3, when Arturo asks Elvira how long they have been separated, Gutiérrez uttered Elvira’s reply, “tre secoli … di tormenti” (three centuries of torture) with pitiful despondency and a darkened coloration on the word “tormenti”. Where Gutiérrez truly excelled, however, was her stunning facility, exactitude and speed in delivering a prodigious amount of fiorituras, trills, runs and roulades (“Son vergine vezzosa”), and doing so with complete naturalness and a loveliness of spirit. In the Mad Scene’s ''Vien, diletto'', she gave not only a brilliant display of note-perfect virtuosity (its second verse was luxuriously embellished), but an imaginative expression of the 'pained ecstasy' for which Bellini asked his Elvira, Giulia Grisi. Gutiérrez is one of the most thrilling and enthralling belcanto sopranos to have graced the operatic stage in recent memory.

Both Amsellem and Gutiérrez succeeded spectacularly in their own ways – the former more vehement, the latter more fragile. The preference shall be a highly personal one. I could not help but feel Bellini would have been pleased with either one. However, judging from the magnitude of pandemonium from the Seattle Opera audience, Gutiérrez was the clear favorite of the two.

The role of Arturo was shared by Lawrence Brownlee (May 10) and Bradley Williams (May 11). Brownlee has the easy high notes for the aria “A te o cara” in Act 1 and “Credeasi misera” in Act 3 and he phrased their long melodic lines with disarming grace and elegance. The gently swaying rubato that informed the cadences of “A te o cara” was especially fetching – no wonder Elvira was so smitten by this Arturo. His attempt at the vertiginous F above high C in “Credeasi misera” was unsuccessful and it came out sounding more like a D-flat instead. Williams, singing on May 11, is a lighter tenor and wisely chose not to attempt the high F at all, although he did a beautiful C-sharp in “A te o cara” which was otherwise marred by wooden phrasing and a lack of passion. To be fair, neither Brownlee nor Williams could muster up enough fiery conviction when declaiming such fighting words as “Questo ferro nel tuo petto” (“I’ll plunge the sword into your chest!”) in the Act 3 finale

As Arturo’s romantic rival, Riccardo presents some of the great opportunities for lyric baritone. Mariusz Kwiecien (May 10) in his Act 1 “Ah per semper.. bel sogno beato” sang with a vibrant, compact tone and a solid high A-flat capping the end of the aria. Later on, in his fight scene with Arturo (masterfully directed by Geoffrey Alm with jangling swords and lots of swashbuckling excitement ), Kwiecien declaimed his lines with freightening venom worthy of a Don Giovanni (One could almost hear his Don threatening Leporello’s life in the Act 1 banquet scene). Baritone Morgan Smith (May 11), a former member of Seattle Opera's Young Artists Program, portrayed Riccardo as a lovelorn warrior through his elegant and suave vocalism. One almost felt for his plight despite his utter incredulity as a villain.

Giorgio is Elvira’s uncle and the most sympathetic character in the opera. The role calls for a true basso cantante with beauty and warmth of tone. John Relyea (May 10) is just such a singer. Relyea’s sizeable bass-baritone carries great weight and authority. He was unfailingly sympathetic in his scene with Elvira and receiving a big ovation for his superb rendering of Giorgio’s Act 2 aria “Cinta di fiori” describing Elvira’s madness. Denis Sedov (May 11) was more a baritone than a bass and did not have the same success with the low-lying Act 2 aria, although he phrased his words with great conviction and feeling.

Completing the cast were bass-baritone Joseph Rawley as Elvira’s father, Lord Gualtiero Walton, mezzo-soprano Fenlon Lamb’s Enrichetta and tenor Simeon Esper as Riccardo’s sidekick Sir Bruno Robertson, all of whom singing their small but vital roles with confident authority. Both Rawley and Lamb are proud alumni of Seattle Opera's Young Artists Program.

Relyea as Giorgio (Left), Kwiecien as Riccardo (Right) in "Suoni la tromba", Act 2

If a general conclusion might be drawn from both performances, it is that the May 11th was primarily a one-star show for Eglise Gutiérrez’s truly outstanding Elvira, whereas the May 10th was an ensemble effort of four similarly gifted artists. Bellini, with sure theatrical instinct, has arranged for his heroine to be heard first from off-stage in a prayer. Gutiérrez’s voice, floating above those of her colleagues’, rang out pure and true. Amsellem’s voice, in the same ensemble prayer, was squally and nearly inaudible. In an ideal world, these would have been my picks for the perfect “Puritani quartet” – Gutiérrez, Brownlee, Kwiecien and Relyea.

In the Italian operas before Verdi, the chorus usually comments from aside, and rarely if ever participates in the dramatic actions. Not so in this I Puritani. Stage director Linda Brovsky made sure that the chorus fill the multilevel steel platforms as fully as possible, as soldiers and peasants. They physically interact with Elvira in Act 1 as she runs around in frantic search for Arturo. They register surprise and pity as she lays on the ground, despondent, launching the great Act 1 finale. Several props are used to show Elvira’s mental breakdown, such as a bouquet of flowers torn to shreds, and a dismantled chess set in the Mad Scene (a brilliant move!) The topnotch Seattle Opera Chorus sang with great enthusiasm and highly cultivated refinement.

Presiding of all of these was veteran belcanto conductor Edoardo Müller, who had received high accolades for his Maria Stuarda in San Diego last February. Müller conducted with a nice mixture of delicacy and drama. The wide range of emotions in Act 1, from tender prayers, jaunty military marches, to the heavenly joy of Arturo’s entrance, were all handled with great élan and seamless precision by maestro Müller. Everything flowed together beautifully between the stage and the orchestra pit.

One final kudos: Seattle Opera has done a great job of educating its audiences by crafting a nice little illustrated booklet called “Spotlight on I Puritani”, a fun, tongue-in-cheek introduction to the opera and its history that will appeal to novices and connoisseurs alike. It is authored by Jonathan Dean, who also does the English supertitles. With such loving dedication, it’s no surprise that Seattle Opera has the highest per capita attendance of any major opera company in the United States.

McCaw Hall's 3000-seat auditorium